A Predatory Creature

A pilfered and underfunded Mexican state preys upon and neglects its people

April 2021

Mexico City and the State of Veracruz

The below is the second piece in a two-part series on Mexico's Covid-19 response and the general state of Mexico's government on a day to day level. Click here to see part one.

Not only has Mexico’s government failed to provide assistance or implement necessary sanitary measures during the Covid-19 pandemic, many in the government prey upon its people. On a highway from Veracruz state to Mexico City, police stop us at a toll booth and thoroughly searched our car. They explain there were reports of weapons and drug smuggling on this route. I ask the police why, if this was one of the most violent nations in the world, they chose to stop us on the way back from the beach. They say it was a random stop. I explain that to protect against discriminatory practices it is important that police have probable cause and a search warrant. My commentary started to annoy them and I backed off.

My friends, young men with long-hair who describe themselves as musicians to the police, are seen as an easy target to find drugs. A discovery of drugs could, in turn, allow the police to extract a bribe. These friends have many stories of bribing police with five or 10 dollars for low-level offenses like driving with an expired license. The police have wide latitude to stop whoever they want which only increases their opportunities for extracting bribes.

After the police search ends and nothing is found, we continue on our way as one friend discusses his time working for the PRI -- one of Mexico’s major political parties -- in the State of Mexico. A PRI stronghold, the State of Mexico surrounds Mexico City. Police officers owe a daily sum to their commanders for the right to patrol. The police in turn extort protection from business owners to pay their commanders. Our friend adds that the most dangerous thing to see after dark in many parts of Mexico is a police car. “People vanish from the streets when the police patrol at night. They will kidnap and extort. If people see a police car, they hide.”

We see police everywhere in each state and municipality. In small towns off main streets we regularly see multiple squad cars. Police are everywhere on highways and at toll booths. Whenever we see police, our friends curse their presence. While walking with my dark-skinned Mexican friend in an affluent neighborhood in Xalapa, Veracruz, a police car pulled up beside us. The police stared at my friend for a good half-minute without looking at me and my white skin. More police often means more insecurity especially for those profiled as delinquents.

Mexican police frequently use excessive force against civilians which leads to murder. In recent years, these murders have led to mass protests across the country. In addition to extorting and terrorizing their own citizenry, many police accept bribes from organized crime.

Our friends say that city police in Mexico make between 250 and 300 dollars a month. The pay is low and if one resists pressure from organized crime they could be murdered. A bribe to augment low pay is often the better option.

Another reason for the corruption are the numerous police departments in Mexico. Every municipality has a department. In addition, there are state police, federal police and the guardia nacional (the law enforcement arm of the military). Another friend, a lawyer, argues that this makes it harder to tamp down on corruption and control the police. “There is no centralized system that controls all the diverse police forces so an anti-corruption campaign is much more difficult. Moreover, police at different levels can be controlled by different politicians like mayors and governors who are in cahoots with organized crime or simply use their local police forces for their own interests.” InSight Crime confirms this analysis and argues that many local police forces in Mexico have become “death squads for mayors with ties to organized crime.”

Our lawyer friend lived in Colombia for many years which, in contrast, has one police force for the entire nation under the control of the national government. Indeed, the public perception of Colombia’s police force is far more positive than that of Mexico’s.

The state is something to milk which in turn allows those in government to milk the citizenry. Our friend who worked for the PRI says people will pay large sums to run for mayor as the PRI candidate. The candidate, who will be elected mayor, then pays a significant amount of their salary to the party.

Citizens who do not support or have connections in the controlling party are less likely to have basic things like street lamps fixed, says our friend. He adds that the state government will also buy building supplies with public money -- like concrete -- and distribute them to neighborhood leaders who secure votes for the party in power. People see that the ruling party controls the distribution of supplies and services. The politicians in government serve who support them. There is no functioning state to assist all citizens.

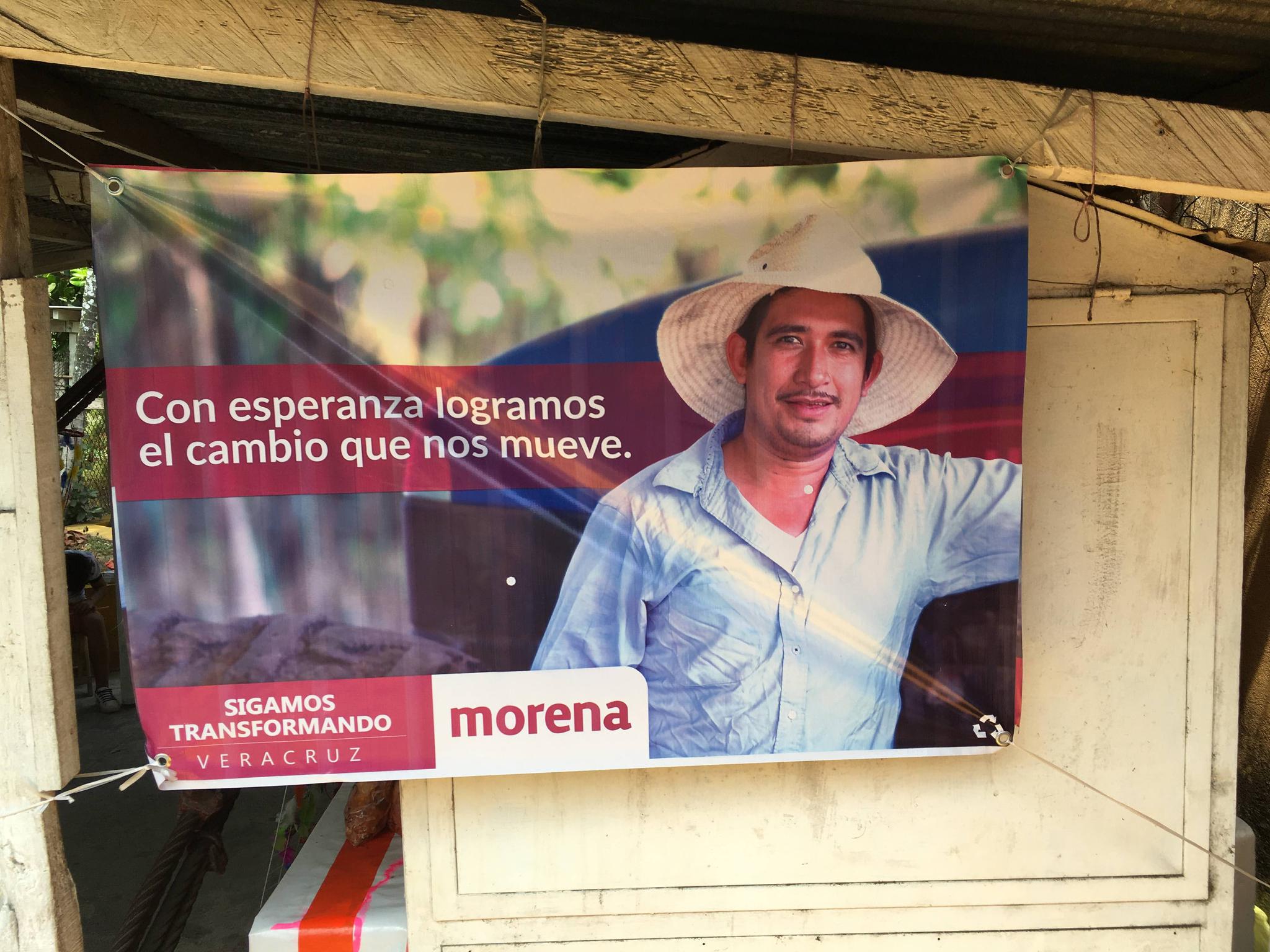

In addition, the buying votes is a long tradition in Mexico. In the election season of 2018, 1 in 3 Mexicans reported being offered cash or other material rewards for their vote. One friend’s mother is a retired school teacher and recalls how many of her students worked for the PRI during election season. For every voter they brought to the polls to vote for the PRI the students would receive payment.

In a country where over 60 million people live on salaries inadequate to buy their most basic necessities, the sale of votes is an opportunity for a bonus every election season. Indeed, some argue that Mexico’s poverty is a major reason it will be hard to eliminate the practice. Moreover, as our friend who worked for the PRI adds, many people work long hours for poor pay with difficult commutes. Caring about politics is not something for which they have time or energy.

The diversion of public resources by political parties is but another example of entrenched corruption in Mexico. Entrenched corruption leads to a lack of public confidence in government and a general acceptance that these are just the way things are. As such, people are less inclined to pay taxes or find ways to avoid paying them (for example, many businesses only accept cash). Indeed, only 60 percent of Mexicans pay taxes and surveys show few are willing to pay the necessary taxes to improve public services. Large companies work hard to evade taxes. The poor then shoulder the burden for basic infrastructure through user fees.

On the four hour drive from Mexico City to Xalapa, Veracruz we pay just under 30 dollars in tolls alone. Thirty dollars is an astronomical sum in a nation where the minimum daily wage is around six dollars. While portions of the roads are well-paved, large stretches are filled with potholes. I relate to our friends that last summer we drove from Seattle to Los Angeles without paying a single toll. They are incredulous.

Nor are public bathrooms in parks, markets and bus terminals state supported. One must pay 25 to 50 cents to use the facilities, a significant part of a day’s minimum wage. Likewise, public green spaces are neglected by the government. In Xalapa, a large park in the middle of the city was overgrown with weeds and high grass and the parking lot’s asphalt cracked and faded. A handwritten sign announces that the park was closed due to Covid-19. Our Mexican friends laugh at how the government has used the excuse of Covid to shutter a park they likely would not have maintained anyways. The scene is all the more ironic given the indoor mall across the street was full of people. A police officer sat next to the sign to ensure the park closure order was followed. No place in Mexico -- one of the world’s most dangerous nations -- is free of the police’s eyes.

The closure and neglect of Mexico’s parks is troubling not just as a symbol of how little the government provides its citizenry but because it deprives its citizenry of a safe and healthy place in which to spend time. Without safe parks for children, where are they to play soccer and get away from a screen? Where are families supposed to spend time together outside of the house if they do not have the money for a nice sit-down meal or a trip to the movies? And even if they do have the money for these luxuries, going to a closed air environment during Covid is a serious health risk.

Back in Mexico City, we walk parallel to a large, forested hill that looks like it would be fantastic for urban hiking. My friend says it is extremely dangerous to go up the hill because of gang activity. I tell my friend how Seoul’s large hills have extensive trail systems and outdoor exercise machines that are well-maintained, safe and widely used. Perhaps not coincidentally, South Korea’s obesity rate is a third of Mexico’s.

The state’s neglect also hampers the tourist industry. In the state of Veracruz, we visit the first Spanish settlement in Mexico, La Antigua. Given its history, it is a natural tourist destination and even on a weekday there are a decent number of tourists looking at the conquistador Fernando Cortez’s home. There is, however, no place to stay in the town. The only hotel was destroyed a decade ago in a major hurricane and never rebuilt. It is now overgrown with weeds. The closest hotel is in Veracruz city, 30 miles away.

The saddest part of the public neglect is that there is significant wealth in Mexico. It has vast oil wealth that generates government revenue. One of the world’s richest men, Carlos Slim, is Mexican. Mexico is the 16th largest economy in the world and home to over 100 million people. It has potential.

However, a large part of Mexico’s oil wealth is stolen. Moreover, Mexico is an extremely unequal society where 40 percent of Mexico’s wealth is concentrated in 1 percent of the population. Mexican companies pay a far smaller share of their profits in worker wages than their European counterparts. The low wages in Mexico, of course, are a reason many U.S. companies manufacture in Mexico in the first place. Inequality in Mexico is part of global inequality. The point, however, is the resources exist in Mexico to better fund basic infrastructure but are not used for such ends.

The Mexican government is both a neglectful and predatory creature. A government, however, is made up of people. It is funded and defunded by people, too. It is elected by people who, in theory, can make changes if they care (the reality is messy, given the level of intimidation and violence toward elected officials and the desperate poverty of many voters who lack the time to be active or are easily tempted to sell their votes). Until the culture of corruption, tax evasion and acceptance of a highly unequal society changes, Mexico’s government will continue to prey on its people while offering little in return.